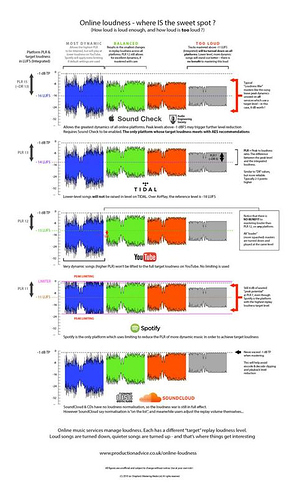

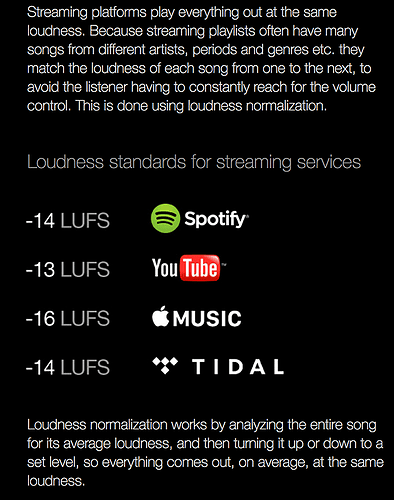

There are conflicting statements in this thread about what happens to quiet audio when transcoded by YouTube. The current state of things (always subject to change with YouTube) is that loud videos are turned down, but quiet videos are not boosted up to the reference level. It would not be possible for dark moody videos to sound quiet if YouTube boosted everything to -13. YouTube assumes that if you mixed your audio under -13 LUFS, you did it for an artistic reason and they’re not going to mess with your art. It’s a different mindset than the broadcast world. Ian Shepherd has previously written about this, and I can verify it with my wife’s cooking videos:

http://productionadvice.co.uk/youtube-loudness-normalisation-details/

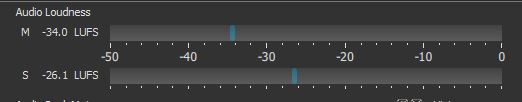

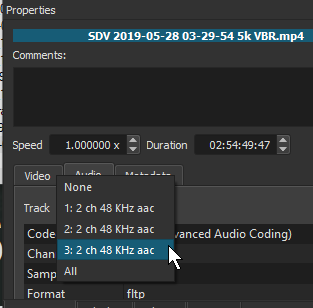

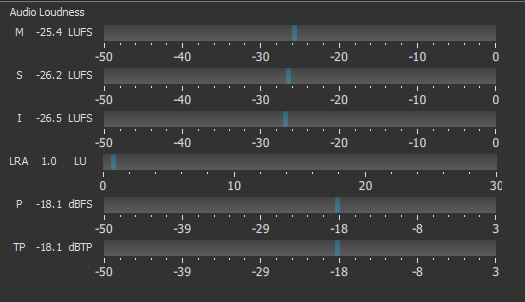

In the Stats for Nerds box (in the right-click menu), the audio is reported 3.1 dB below the -13 LUFS reference level, meaning the integrated source is -16 LUFS (which matches our master file). But normalized playback volume is still only 100%. It would take more than 100% to get the -16 LUFS source up to -13 LUFS. Ripping and integrating the YouTube player’s audio is also below -13 LUFS as expected.

So what’s an easy way to get Shotcut audio up to -13 LUFS?

When I have time to be an editing purist, I like the workflow of exporting speech stems to a DAW to make things pretty, then bring a consolidated stereo file back into Shotcut before the final export. I did this for my wife’s early videos, but then she got so efficient that she could edit video faster than I could mix audio in my limited free time.

Luckily, since my wife’s cooking studio (which is really just our kitchen that no longer functions as a normal kitchen) is such a known and consistent entity, volume leveling can be done directly in Shotcut and sound pretty much as good as a DAW for simple things. Here is the filter chain we have been experimenting with in Shotcut for speech tracks so that she can do full video and audio production by herself. (This is the same woman who edited a 40-minute documentary using Shotcut on Linux two years ago. Yes, I know I married a rare gem.) The first filter for speech tracks is:

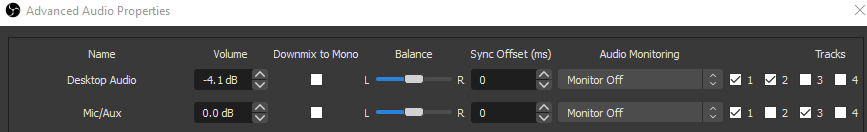

Gain/Volume: This is to get the audio within 5 dB of the target -13 LUFS level if it starts out too quiet. Watch the short-term loudness (the “S” bar) on the loudness scope to help with setting the gain. Don’t go for the full -13 LUFS yet.

High Pass: When raising gain, we also raise background noise like air conditioners. For female voices, the cutoff frequency can often be set as high as 200 Hz without impacting speech.

Limiter: This filter prevents clipping distortion due to the Gain filter. We usually set the limit to -3 dB.

Compressor: This filter is for making the audio smoother, as opposed to rapid gain adjustments for level compliance. We give it a 1:3 ratio with a -19 dB threshold and +3 dB makeup. We also change the attack to 50 ms and the release to 300 ms. However, this is dependent on the percussiveness of your presenter’s voice.

Notch: Optional. Our room has resonance that causes a buildup at 3.2 kHz, so we add a notch at 3200 Hz with a bandwidth of 50 Hz and rolloff of 6 to minimize it. The result has less echo and shrillness.

Then we preview the audio (including music now) and go back to the Gain filters. We adjust them (speech and music) to try to get the short-term loudness on the meter close to the -13 LUFS spec while also being balanced well to each other. Short-term loudness held to spec over time will cause the integrated loudness to be the same number. But short-term loudness provides much faster feedback on the scope about how close you’re getting to spec. Still keep an eye on the integrated level, though.

The filters listed so far go on individual clips or, more ideally, an entire track head. They are rather robust as general purpose settings, but will of course require tweaks for your exact environment. Be aware that you can only raise the Gain so far in this configuration because the Compressor will start squashing whatever extra gain you try to push. If you want a squashed sound, great. But if what you’re really wanting is more volume that pushes the edge of distortion, then increase the Compressor’s makeup gain instead of the first Gain/Volume filter.

Lastly, we apply a Limiter filter to the master track in an attempt to keep true peaks below -1 dB. To achieve this in reality, the amount needs to be -1.5 or -2.0 to allow for slight overages since the limiter is measuring sampled peaks rather than true reconstructed peaks.

Extra tip: When people mix speech tracks with music tracks, they often create a “swell” in the human voice range of the spectrum because all tracks are contributing to that range (music has sounds in the speech range too). This hot spot in the spectrum is bad news because normalizing the finished audio will cause the speech range to top out before the rest of the spectrum can top out, meaning your bass guitars and high-frequency sound effects will sound unnaturally quiet compared to the doubled-up speech range. This spectrum imbalance makes it harder to “sound loud” even though you’re punching at -13 LUFS. The solution is to create a hole in the music tracks so that music and speech don’t combine to make that part of the spectrum sound twice as loud as it should be.

To do this with Shotcut filters, mute everything except your speech track, then play it back while watching the Spectrum Analyzer scope in Shotcut. Notice which bar in the graph is consistently taller than the rest. (Widen the window dock so you can see every label on the graph.) For my wife’s voice, she usually talks at 500 Hz. Next, we go to the music tracks and add a Notch filter with a center frequency of 500 Hz (or whatever your fundamental speech frequency is) and a bandwidth of 150 Hz. This reduces the volume of the music in the frequency range that your voice is talking in, effectively creating a “hole” in the music for your speech track to fill. Now, when speech and music are summed together, you maintain an even frequency spectrum instead of doubling up in the speech range. This lets you raise the overall volume louder than you normally could, and most importantly, increases the intelligibility (clarity) of the speech because the music isn’t drowning out the speech anymore.

If anyone happens to visit my wife’s channel, could you leave a shout-out that Austin sent you so she knows I’m supporting her?  Thanks! And yes, the video was mastered and uploaded in 4K as an H.264 CRF 16 file (Shotcut quality 68%) to get the higher bitrate from YouTube, but that’s a discussion for another thread.

Thanks! And yes, the video was mastered and uploaded in 4K as an H.264 CRF 16 file (Shotcut quality 68%) to get the higher bitrate from YouTube, but that’s a discussion for another thread.

).

).

.

.